A’Lelia Bundles – Courtesy of Indianapolis Monthly Magazine. Used with permission.

As America undergoes a cultural reckoning after the massive protests following the heinous murder of George Floyd and other unarmed Black individuals at the hands of police, the history of our country has been undergoing a long-delayed re-examination of history. Prior to the social upheaval, Black history has been largely ignored in textbooks and relegated to the month of February, which now seems a blatant, if not paltry and highly inadequate, gesture. Fortunately, in an effort to overcome the dearth of content related to Black history and historical figures, Black authors, directors, producers, screenwriters and actors have all worked tirelessly to tell the stories of their ancestors. And because of their fearless and enterprising efforts, the historical and cultural contributions of Black Americans are increasingly reaching mainstream audiences via literature, theatre, film, television and the internet.

Representing the upper echelon of Black creatives making a difference, especially during this time of cultural revolution, is Indianapolis native A’Lelia Bundles. A journalist and news producer, whose career spanned 30 years, Bundles is now a renowned author, best known for her biography of her great-great-grandmother Madam C.J. Walker titled “On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam C.J. Walker.”

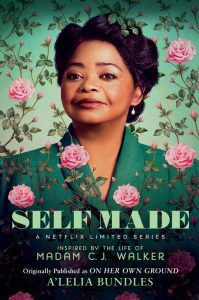

Bundles’ bio on her groundbreaking subject was adapted into a limited TV series titled “Self Made: Inspired by the Life of Madam C.J. Walker” that premiered on March 20 on Netflix and continues to be streamed on that platform. The series starred Academy Award-winner Octavia Spencer as Madam C.J. Walker, the Black haircare pioneer and mogul, who overcame great odds in hostile, turn-of-the-century America to become the country’s first Black, self-made, female millionaire.

Bundles’ extensive resume reflects someone who has more than lived up to her famous ancestor’s storied legacy. A 1970 North Central High School graduate, Bundles graduated from Harvard and Radcliffe Colleges in 1974 and received a master’s degree from Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism in 1976. Her first stint in television was as a producer for NBC Nightly News in New York. Later, she was a producer and executive with ABC News.

Daughter of the late A’Lelia Mae Perry Bundles, vice president of the Madam C.J. Walker Manufacturing Company, and the late S. Henry Bundles, Jr., I first met Bundles in the late 90s through her father, a friend, who at the time was president of the Center for Leadership Development in Indianapolis. But my ties to Bundles and her family actually go back further to the late 70s when I worked at RTV6, where I produced a program titled “Nine Leaves on a Sprig: The Story of Madam C.J. Walker.” A half-hour special, it was the very first television program about the iconic trailblazer. Later at Channel 6, I produced a special about Madam Walker Legacy Center, where, upon Bundles’ recommendation, I served on its board of directors.

Over the years, Bundles and I have maintained regular contact, but most recently, we reconnected in person in September at the opening of “You Are There 1915: Madam C.J. Walker, Empowering Women,” an exhibit currently on display at Eugene and Marilyn Glick Indiana History Center until January 2021. The IHS houses a major collection of both Madam Walker’s and her company’s documents and papers.

Recently I read a candid, revealing and critical response to “Self Made” in a May 12, 2020 article she wrote for theundefeated.com, I was eager to compare notes about the series, which not only fictionalized, but also caricatured Bundles’ narrative. Also,in light of recent events, I thought it would be especially interesting to my readers, given Bundles’ credentials as a journalist and historian, to gain her perspective on the Black Lives Matter movement and related topics. Following is an edited transcript of our phone conversation from Bundles’ Washington, D.C. home and an email exchange that took place earlier this week.

What did you think when you saw the series for the first time?

When I went to the screening in L.A., I was in the room with the showrunners and a few of the executives. It was a lovely screening room on the Warner Brothers lot. They were going out of their way to make me comfortable, but I think the executives did not really know how contentious my relationship with the showrunners and the writers was because they had given everybody else the impression that I was on board, but they knew I wasn’t. I gave them notes and I had been telling them all along what was wrong with it. I had another meeting where I told them what was wrong with it, so they were not surprised and then I did my best not to put my thumb on the scale during the first week it ran because I wanted to see what other people said and once I did, I felt validated.

When I went to the screening in L.A., I was in the room with the showrunners and a few of the executives. It was a lovely screening room on the Warner Brothers lot. They were going out of their way to make me comfortable, but I think the executives did not really know how contentious my relationship with the showrunners and the writers was because they had given everybody else the impression that I was on board, but they knew I wasn’t. I gave them notes and I had been telling them all along what was wrong with it. I had another meeting where I told them what was wrong with it, so they were not surprised and then I did my best not to put my thumb on the scale during the first week it ran because I wanted to see what other people said and once I did, I felt validated.

Did you have to sign a non-disclosure agreement (NDA) that you would not criticize the Netflix series?

I had a lawyer look at it because I wanted to make sure I was not going to be circumscribed in any way if I spoke up. I did what journalist do. I documented everything and I had been telling them all along what the issues were going to be and a couple of people just kept gaslighting me, thinking they could just tell people whatever and everybody would buy their deceptions.

When I completed theundefeated.com article, I called Warner Brothers’ publicity, the people with whom I had been interacting, to give them a heads up. They knew what was wrong with the series because their friends had been telling them, so I gave them an opportunity to respond. The showrunners did not have any response because they knew what I had written was accurate and much of the audience was agreeing with me. The response to my article has been great. People who know me and read it knew what was going on. and there have been a lot of Hollywood people who have reached out to me quietly in support.

What do you suppose the agenda of the series creators was?

The question is, who were they trying to please? Also, the woman who was the head writer, who is Black, as were the showrunners, was projecting her own issues in the story.

What are you working on now?

I was doing lots of interviews on the Netflix series, but have since pivoted back to writing my new book, “The Joy Goddess of Harlem: A’Lelia Walker and the Harlem Renaissance,” which will also be published by Simon & Schuster in 2021.

Any plans to revisit Madam Walker’s story in other projects?

Any plans to revisit Madam Walker’s story in other projects?

Nothing specific. It is my intention to continue telling the stories of Madam Walker and A’Lelia on other platforms and to correct the misinformation that was presented in “Self Made.”

What are you learning during the pandemic?

That inequality is rampant and people who already have means will continue to protect their interests and insulate themselves as much as possible from the suffering of others. The flip side is that there are many Americans who are willing to assist their fellow citizens.

Shifting gears and with all the interest in why Black Lives Matter, what was it like for you growing up in Indianapolis?

We were certainly financially comfortable. I grew up privileged, in the sense of having educated parents, who never worried about what their jobs were going to be, but I was also surrounded by an extended family in which other people struggled. My father had eight siblings and he and his older sister are the only ones who finished college, so most of my relatives worked at Chrysler and Ford and Lilly in jobs that were not necessarily white collar. My father’s parents were poor. My grandfather worked on the railroad and my grandmother was a housekeeper at Fort Benjamin Harrison. Like many Black families, the level of affluence is different, as is the range of opportunity, education and financial means among members.

How did your parents prepare you for the effects of racism?

If someone said something derogatory to me at school, my mother’s response was “They are the ones with the problem.” My mother became the president of the PTA when there were probably fewer than 50 Black kids in school and she was always present. My father traveled a lot and wasn’t present in the way she was. When I was applying to colleges when I was at North Central, some of my teachers were excellent. I got a great education. I applied to Northwestern, Harvard, Barnard and others and was not applying to any Indiana schools and the counselor said to my mother, “Well, Mother, do we really want to spend this money?” and her reply was, “First of all, I’m not your mother and second of all, it’s my money.” My mother and I determined the counselor was not only racist, he was lazy and did not want to fill out the paperwork for these out-of-state schools that required more than checking off a box if I had gone to IU. The fact that I was a good student and got along with people made a difference. For the most part, I had a really positive experience in Washington Township Schools, despite other incidents that took place.

What were they?

I was elected vice president of student council on the same day MLK was assassinated. It resulted in some white parents calling the school upset at me having been elected, but I had the support of teachers and others who rallied around me and tried to protect me. And when I ran for president of student council the next year, there was a lot of racism and someone called out during my speech and booed me. There was a definite sense of “We are not going to let her get to that next level.” So, there was a of that stuff going on. Also, I wore an armband on Moratorium Day and there was a government teacher, who was in the American Legion, who tried to have me expelled. Ninety percent of my experience in Washington Township Schools was positive. I had great teachers, who were really supportive, but there definitely were racists who were part of that scene. There was a lot of racism at play in tracking students academically in extracurricular activities, like sports, music and drama.

A’Lelia Bundles – Courtesy of Anya Chibis. Used With permission.

What about your experiences with racism in your professional life?

There was one point early in my career when I was in the NBC Houston Bureau. I worked with a really great group of people, a great bureau chief, camera crews. George Lewis was the correspondent. They were all really supportive and great mentors for me. But as time went on, they had all moved on. The person who became bureau chief was white and was really mediocre. Mediocre white guys get to move up because their friends protect them. He had been a film editor and some of his buddies who had worked with him were executives. He eventually became the bureau chief in Chicago and had screwed up some major story. They were protecting him, and rather than firing him, he was moved to Houston which was a smaller bureau. I was his producer and this guy was so racist and so mediocre, but in his heart felt he superior to me because he was white. I was miserable. He would go out on his boat on the weekend and leave me to do all of the work he should have been doing, so I began to figure out my exit. I knew I had to get the hell out of there and I planned. I made calls to New York. Finally, the new president of the news division happened to be visiting the bureau. I had a conversation with him and I don’t know if I presented my case so strongly or because of my allies in New York, but in less than a month, I was gone from that bureau.

It sounds like you found effective ways of working around racism during your broadcasting career.

I would say to myself, “I see what you are doing. I see who you are. I am just going to move on and figure out another way to do what I have to do. I am not going to allow you to make me crazy.” Part of my method of retaliation was not to blow my top. I would make a decision to leave and in 90 days and decide “I don’t want to be here anymore. I am going to put aside a little extra money. I am going to make a plan, have a strategy, and I will leave when I am ready to leave.” I have left a couple of positions and have found other things when I have decided I am just not going to take it anymore. You are mistreating me and I am not going to cuss you out, but you can believe I am going to move on.

What do you hope the Black Lives Matters movement will ultimately accomplish?

That’s an impossible question to answer! America has really shown there is no end game to the pursuit of civil rights and social justice for African Americans. The recent murders that have focused attention on police brutality and white supremacy are not new. What BLM is saying is not new.

I’d like to be hopeful, but I can’t help but be a bit cynical because these same issues and crises existed 50 years ago when I graduated from North Central High School. When Martin Luther King was assassinated, we hoped America would do better. When Barack Obama was elected president, some people — though, not I — wanted to delude themselves into thinking America was “post-racial.” We could say that when the 13th, 14th and 15th Amendments were passed that African Americans would receive equal treatment under law. But as has happened over and over again in American history, the backlash of white resentment erupted. All one has to do is listen to the words of the current president’s defense of “heritage” and Confederate statues to witness the strength, intensity and depth of the backlash.

What will it take for change to finally occur?

While I’m glad that many people who were in denial about this reality are now paying attention, I’m not entirely convinced the majority of Americans will really change their attitudes, their views and most importantly, their behavior. At this point, the most important change that could come would be the acknowledgment by white Americans that racism and white supremacy are baked into the history of America. Some self-education on American history would be a great start.

Honestly, until large numbers of white Americans open their minds and become willing to learn American history and the legacy of systemic, legally sanctioned discrimination in education, housing, health care, employment, etc., very little is going to change.

Did the protests offer you any hope?

It really is interesting to see the coalitions that are developing. Then to see the teams at NASCAR at the track walking with Bubba. And then there was the Washington Post article about the number of Asian and Latino young adults who are trying to persuade their parents to take another look. To see people in small towns protesting. That is giving me hope. For a long time, you couldn’t say “racism” and people would just dismiss it out of hand. There does seems to be a recognition that there is systemic racism, so I think it may be different. My generation was impatient, but the current one is less patient about hearing the same old thing over and over again.

For more information about A’Lelia Bundles, go to aleliabundles.com or follow her on Facebook @aleliabundles.author or Twitter and Instagram @aleliabundles.